So now that we've got that already established connection out of the way let's throw in a third film, my personal pick for most underrated movie of all time: Twin Peaks - Fire Walk With Me. Fire Walk With Me has got to be the most hated of all in Lynch's filmography (except maybe Dune) largely because it frustrates fans of the TV show while, for fans of the director himself, it doesn't stand on it's own the way a proper movie should. I could write until the cows came home about why, when watched on it's own terms, the film is a lost masterpiece but I'll also save that for a later date. Instead I want to start connecting the dots between the three movies.

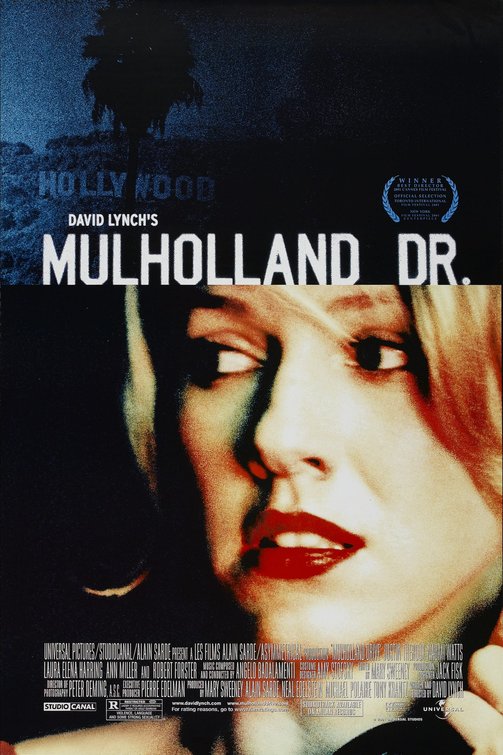

The most obvious and important point to raise is that these films all make up a very clear style that occupied Lynch for about a decade. It's interesting to note that while only one of these films is widely respected, together they codify so many of the visual tropes associated with Lynch: the strobing effects, the red curtains, the ominous smoke and so-forth. Besides the odd detour that is A Straight Story, these three make up a decade for Lynch and there's an extremely clear stylistic line to be drawn though all three. Many would throw in Inland Empire, discard Fire Walk With Me and dub the result the LA Trilogy but I'm disregarding Inland Empire because it's standard definition video format creates too much of a jarring visual contrast with the others.

I've already pointed out how Mulholland Dr. and Lost Highway are essentially telling the same story and while Fire Walk With Me is clearly the odd one out there's no shortage of parallels between the narratives. First of all David Lynch has stated that Lost Highway and Twin Peaks share a fictional universe, which could go for any of his films but I'll take what I can get. More importantly, Fire Walk With Me begins the trend of Lynch placing a chunk of narrative at the beginning or end of the film which, on the surface, is a different story to the main plot. The Chet Desmond sequence is less explicitly connected; it's not a representation of Laura's subconscious and no characters from the 'main' story are recast in different roles. However as a structural device it is still an important precursor to Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr.

Fire Walk With Me also reconfigures the use of BOB and The Man From Another Place, which has a profound effect on how Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr. unfold. In the Twin Peaks TV series, there is a very distinct and, for Lynch, defined mythology being created. In Fire Walk With Me these two other-worldly creatures are more intrinsically tied into Laura and Leland's psych. Whatever metaphor you wanted to extract from their presence in the show it was clear that they existed as independent entities within the hazily defined logic of the Twin Peaks universe. In Fire Walk With Me this is less clear; BOB is strongly hinted to be how both Laura and Leland repress the most hideously confronting aspect of their relationship. In Lost Highway we are given a character that plays an extremely similar role in the Mystery Man who acts as both Fred's guilty conscious in the beginning of the film and the devil on his shoulder during the bloody climax. In Mulholland Dr. we have the monster behind the diner and the cowboy who externalise the hidden guilt and fears of the characters. What's important to note is that none of these figures are entirely bound to the characters whose subconscious they are supposedly representing. They could just as easily be described as spiritual entities who abide by their own metaphysical rules. This is largely because in David Lynch's world the subconscious is the spiritual and these figure are, for lack of a better term, the gods of dreams, as stupid as that may sound.

Fire Walk With Me also reconfigures the use of BOB and The Man From Another Place, which has a profound effect on how Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr. unfold. In the Twin Peaks TV series, there is a very distinct and, for Lynch, defined mythology being created. In Fire Walk With Me these two other-worldly creatures are more intrinsically tied into Laura and Leland's psych. Whatever metaphor you wanted to extract from their presence in the show it was clear that they existed as independent entities within the hazily defined logic of the Twin Peaks universe. In Fire Walk With Me this is less clear; BOB is strongly hinted to be how both Laura and Leland repress the most hideously confronting aspect of their relationship. In Lost Highway we are given a character that plays an extremely similar role in the Mystery Man who acts as both Fred's guilty conscious in the beginning of the film and the devil on his shoulder during the bloody climax. In Mulholland Dr. we have the monster behind the diner and the cowboy who externalise the hidden guilt and fears of the characters. What's important to note is that none of these figures are entirely bound to the characters whose subconscious they are supposedly representing. They could just as easily be described as spiritual entities who abide by their own metaphysical rules. This is largely because in David Lynch's world the subconscious is the spiritual and these figure are, for lack of a better term, the gods of dreams, as stupid as that may sound.This spiritually transcendent approach to the subconscious is what makes these films, and Lynch in general, so difficult to unpack and 'solve'. You can never truly separate the 'dream' parts of the films from the reality because the manifestations of the characters' repression coexist with the traumatic events that supposedly created them. The cowboy, the director and the monster behind Winkies should have no bearing on Diane's 'real' life but they do. The police shouldn't be investigating Pete Dayton at all by the end but they are. And similarly the FBI shouldn't be aware of the black lodge or it's inhabitants but as the TV show repeatedly makes clear, they certainly are. It's this constant refusal to draw a clear line between the real and the subconscious that makes these films continually frustrating but also keeps them powerful for years to come. Every attempt to lay out the meaning of any of the films beat by beat is always going to be flawed because of this. No matter what people tell you, they'll never have 'the answer' even if one's interpretation pieces enough of the film together to be moved by the characters and their plight.

When these two, seemingly contradictory, worlds can coexist then you end up with mobius strip narrative that all three make up. It's most explicit in Lost Highway as Fred is revealed to be the one who gave himself the message that 'Dick Laurent is dead' earlier in the film. This works with the highway motif of the rest of the movie where guilt is shown as an endless chase that finds Fred back at the same place he started. The callbacks to various scenes and characters throughout Mulholland Dr. could be explained away as re-imagined figures in Diane's life but many still consider it a cyclical narrative. Diane's death takes us back to silencio, to the monster behind Winkies and most obviously Rita and Betty discover Diane's rotting corpse about halfway through the movie. If one wanted to be really prosaic with their interpretation then it is entirely possible to see Mulholland Dr. as a perfectly linear narrative, no matter how weird. Whichever way you choose to see the film, Lynch is still employing a similarly cyclical structure to Lost Highway, it's just less explicit. Fire Walk With Me is also structured as a mobius strip but it's a much bigger, more complex and ultimately more perplexing one. This is most obviously due to the 20-odd hour backstory it has accumulated from the TV series. Fire Walk With Me is largely a prequel to Twin Peaks but it is frequently seen as a sort of conclusion to the Twin Peaks mythology, albeit an unorthodox one. When taken with the TV series' Fire Walk With Me becomes a lot closer to Lost Highway's narrative, where the end is the beginning. But this isn't merely a comment on Fire Walk With Me's chronological relation to the TV series that spawned it, there are quite a few downright weird time lapses that still perplex me. Laura dreams of visiting Cooper in the Red Room/Black Lodge, it's unclear if it's his dream from episode four or his fateful visit from the finale, and when she awakes Annie, whose not showing up for a while in the internal chronology, warns her about the events of the finale. To make matters even more confusing the final scene sees Laura meeting Cooper and an angel in the Black, or perhaps White, Lodge. There's something perversely moving about Cooper and Laura, two people swallowed by BOB and the town itself, comforting each other in death or wherever the hell they are. However it is still almost impossible to extract exactly what this means for either character. But it very clearly ties back to the mobius strip of Lost Highway and Mulholland Dr. Just as Fred gives himself the message that kickstarts his journey, Laura arrives at the conclusion of Cooper's journey which, paradoxically, her own death kickstarted.

Hopefully I've demonstrated how these films form a sort of conceptual trilogy but I think they have a nice overarching narrative that tie them all together. I doubt Lynch ever intended them to work like that but they do. In Fire Walk With Me we are given a mercilessly claustrophobic small town, the seedy inverse of what we'd seen most of the time in the show. It's what would happen if we never left Frank and his goons in Blue Velvet. Laura is trapped, she's doomed to become a victim of Twin Peaks, her father and the nasty spirits surrounding both. This experience is the common frustration of many young people in small towns taken to the most hideous of extremes. The escape never comes but in a weird way Lost Highway is the escape. If Fire Walk With Me represents the imprisoning nature of where we start then Lost Highway shows the equally poisonous nature of the road in-between, quite literally. Laura suffers for staying while Fred suffers for running. Unsurprisingly then Mulholland Dr. represents the arrival and the devastating disappointment it can create. The film begins with the arrival of Rita, who may as well just have come off of the lost highway, and then we see Betty's much sunnier entrance into Hollywood. The climax of Mulholland Dr. is the most finite of the three and serves as a fitting conclusion to what began in Fire Walk With Me and Lost Highway. Taken together these three films each depict a stage in a single journey, exposing the unique nightmarish quality in each.

So, for future reference I'll call these three the 'denial trilogy' because repression could sum up pretty much all of Lynch's work. Each film shows two distinct nightmares: one is allegorical and fantastic while the other is the brutal reality the first is trying to hide. It's important not to dismiss the first as merely a figmant of a character's imagination but they clearly help to illuminate each protagonist's subconscious. Because the mysteries of the black lodge, the perilous affair with Alice and the mystery of Rita's car crash are not as horrifying as Leland's abuse, Fred's guilt and Diane's bitter jealousy. While Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks (the series) showed two shades to the same reality, the denial trilogy (sounds good doesn't it?) shows two separate realities that are both black. Confronting the darkness that is unquestionably 'real' is devastating but by filtering the corny fifties Americana that the protagonists imagine through a uniquely creepy perspective, Lynch makes sure the audience never loses sight of the dangers of repression. There is no better world in the dichotomy of each film, merely two different sorts of pain.

I feel like I should finish this post by confessing why I am really so hell bent on creating a unified experience out of these three movies. I stand by everything I've said but part of me just wants to avoid picking favourites. When someone asks me what my favorite Lynch film, or my favorite film in general is then I don't want to be forced to pick a favorite amongst these three that I really love. I'd rather just mysteriously answer The Denial Trilogy, possibly backwards, and let the confused person who posed the question try and work out exactly what that means. And that confusion will be all the explanation for why these films are so strong.

Or they could just read this stupidly long post, whatever works best.

Very awesome article! I agree with so much of what you have written.

ReplyDeleteI saw Twin Peaks FWWM before seeing any episodes of the TV show and I loved it. After watching the series twice in the past ten years, I love it even more.

As an artist myself, one of the biggest influence in my work is Lynch. And what I take away from him the most is his, as you put it, "constant refusal to draw a clear line between the real and the subconscious that makes these films continually frustrating but also keeps them powerful for years to come."

To me, in art and in life, there is not a clear line between ordinary reality, and non-ordinary reality (the world of dreams, subconscious, fiction, movies, etc). Of course this computer is real in way that my subconscious isn't, but aren't all the words I'm typing filtered through, maybe even driven by/inspired by my subsconscious? And isn't the fact that I even showed up at this site because Lynch's 'fake' movies moved me so deeply that 20 years after seeing Lost Highway I still seek out discussions about it? These non-real things Lynch deals with drive actions, and the result of said actions become real world things and relationships and behaviors.

So to me, Lynch is right in not drawing that clear line. There isn't one. Ideas aren't tangibly real, neither are feelings, but they drive the world forward, and backwards. Life is a moebus strip. What happens to Betty IS what happens to Diane. We want to label them as different, or real or not real, but there really is no distinction as far as Diane in concerned.

Lynch turned me on to this way of seeing art, and the world in general. If you can get to the point where you stop needing to define things as either real or not real, his movies make perfect sense. I don't struggle with them at all anymore.

Lynch gets it in a way that almost no one else does. Werner Herzog spoke about the difference between truth and fact. Lynch gets at the truth of a character's existence - not the factual content of their 3D world.

I wish he'd make another. Bravo to you on this great article. Look forward to more from you guys.

Thanks so much for reading and commenting.

ReplyDeleteI also really hope Lynch makes something else soon but I'm not quite sure how it would go at this stage. I like Inland Empire in many ways, particularly the way the narrative threaded together even more intricately then FWWM/LH/MD, but it didn't have anywhere near the visual punch of these films. I suppose if he can strike a balance between the fluidity of Inland Empire and the visual strength of these three then we could have another masterpiece. Who knows?

Also if you're interested in Mulholland Dr. we did a podcast on it a year ago. Its a bit scattered and all over the place... but that kind of fitting.